| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| a better burger |

|

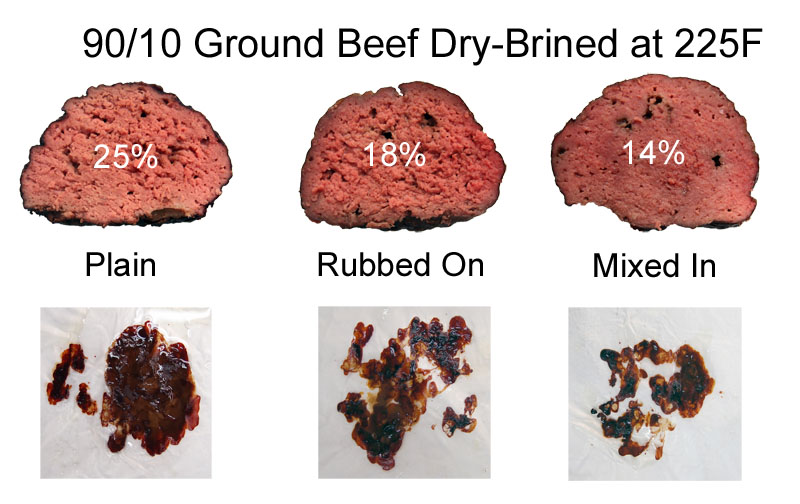

Jan 2012 The perfect burger is an unobtainable goal, if merely because each person has a different vision of what a burger should be. Thin, well-done and crispy? Thick, juicy and pink? Unadulterated beef, or meat enhanced with onion soup mix and moistened bread crumbs? Served on a bed of onions, cheese lettuce and tomato? Or hidden under a mound of barbecue sauce and fried onions? The list is unending, and often unnerving. Leaving everyone free to claim the best burger in the city. Now, *MY* perfect burger is a 70/30 mixture of ground chuck and short ribs. I like to partly freeze 1/2" cubes of meat and "grind" them in a food processor. Gently form into 3/4" thick patties, and sear for a minute or two on both sides over a blistering hot coal fire. Then let the interior warm up to 125F on the side of the grill indirectly heated by warm air. No additives other than salt, and nothing on the toasted bun other than burger. Pink from end-to-end. And don't forget to use a thermometer- an error of just 5F is the difference between tasting like steak or meatloaf. But, if the only flavoring on my burger is salt, when should you salt and how much? It turns out salting is more than just a matter of taste, it also dramatically affects texture and juiciness. For a test, we compared three 8oz (225gm, 3" diameter) balls of 90/10 ground meat (the low fat content makes it easier to separate moisture loss from rendered fat- this is kitchen science, not dinner). One sample, the plain control, was simply formed into a sphere. A second lump was formed into a sphere and sea salt (at the 1% by weight level) was shaken over the exterior. And finally I took 8 oz of loose ground beef, drizzled on 1% salt by weight, and then gently formed into a ball. After allowing the salt to diffuse into the meat for an hour in the fridge, they were carefully weighed, and then cooked in a 225F oven until each sphere reached 150F- still below the USDA approved "safe" temperature of 160F for ground meat, yet above my preference of 130F1. As you can see from these cross-sections, the rubbed on salt (middle image) penetrates about 3/8", causing that surface layer to congeal, destroying the iconic, crumbly texture of ground beef. The internally-salted sample was converted entirely into a less porous, moist gel that is exactly unlike steak. But definitely meaty (something to consider when you add salt, or salty liquids like soy sauce, to meatballs or meatloaf. When to salt matters.)

The numbers in white indicate weight loss (fat plus moisture) 15 minutes after cooking, while the square images are photographs of pan drippings captured under each ball. The 15 minute rest period is critical. While the "Rubbed-On" and "Mixed-In" weight losses measured immediately after cooking were essentially identical, when measured 15 minutes later, the "Rubbed-On" sample continued to ooze liquid from the unsalted interior. Almost a quarter of its total weight loss occurred during the 15 minute resting period. These moisture-preserving benefits depend on the final cooking temperature and salt content. At low temperatures, below 100F to 130F, muscle fibers have not yet unwound. So, in any case they would not squeeze out liquid, and salt's only role is as a tenderizer and flavor enhancer. However, above 130F juices begin oozing out robustly. More than 90% of all water is contained between the muscle fibers. Salt creates small electrostatic barriers, and these barriers help bind the water to the muscle matrix (for more details, see this article on salt brining). Below 2% salt, the sodium ions help muscle fibers attract water, and hold onto that water, at least for a while. Above 2%, the salt ions break so many muscle fibers, the ends reconnect, forming a dense jell. Oddly dense, given how little water was lost. Medium-texture ground meat produced by a food processor instead of a meat grinder, will sometimes will fall apart on the grill. So a bit of salt helps bind the meat together. An alternative (see the brining article above) is to add a tiny bit (1/4 to 1/2 tsp) of dried meringue to each burger. The egg whites rehydrate and form a protein glue which adds little flavor but retains moisture without affecting texture. Either way is fine. So my burger advice is to add a small amount of salt just before cooking (e.g. about 1/4 tsp of salt per pound of meat), then form the patties, then grill immediately. Sprinkle a bit more salt on the crust right off the grill, place on a buttered and toasted bun, and enjoy.

|

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Additional articles on kitchen science can be found HERE. 1 If you cook the burger to 125F, it will continue to carryover a few degrees as surface heat redistributes into the center. Ending up a perfect medium rare. According to the FDA, 130F is too low to avoid the possibility of food-borne illness. But, I rinse my meat under very hot water before grinding, maintain a high standard of cleanliness in the kitchen, and so on. Compared to industrial scale grinding where each pound of meat contains beef (and perhaps bacteria) from hundreds of cows, I feel comfortable this process is safe. But you should draw your own conclusions.

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |