| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| the curious case of the tender shrimp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

March 2014 **PRELIMINARY RESULTS** Any civilization more than 5,000 years old is likely to have a few tricks up its sleeves. Beyond inventing paper and printing, rockets and compasses, noodles and government bureaucracy, China's stir-fry traditions are at the core of some of the most flavorful cuisines in the world.

But stir-frying does have its dark side- it's very easy to overcook food, turning pork strips into shoe leather and raw veggies into gooey globs. Shrimp is particularly hard to cook properly- often 15 seconds is all that separates tender curls of white meat from vulcanized rubber disks.

How does velveting work its magic? There are two hypothesis- mechanical and chemical. Baking soda is a "leavening agent", that is, the NaHCO3 breaks down with heat and/or in the presence of acids to produce bubbles of carbon dioxide. These bubble inflate and lighten the texture of quick breads and cookies.

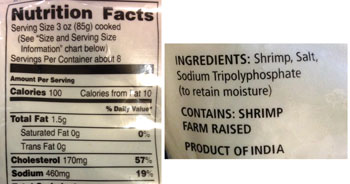

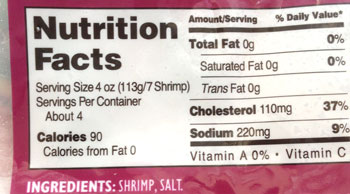

In other articles we've demonstrated that high levels of baking soda form bubbles in meat, breaking apart muscle fibers and tenderizing. Perhaps the smaller levels, typical of velveting in shrimp, has a similar effect. Alternatively, baking soda and lye are both alkaline (pH greater than 7, while meat is typically 6.2 to 7.5). They might chemically break apart the bonds holding muscles together, enhancing tenderness. Or perhaps relax shrimp muscles, so they do not contract as much on heating. Which is complex enough. But there is an additional wrinkle, a by-product of modern shrimp farming. Unlike traditional Chinese markets which sell mostly live seafood, today almost all shrimp is flash-frozen on-board ship or at the shrimp farm. To increase juiciness, shrimp is often brined in salt water at the factory. Or dipped in sodium bisulfate to prevent black spot. Or marinated in sodium tripolyphosphate to reduce drip loss- e.g. water loss from bloated iced meat cells that burst when defrosted. For example, see this label from shrimp sold at a high-end market:

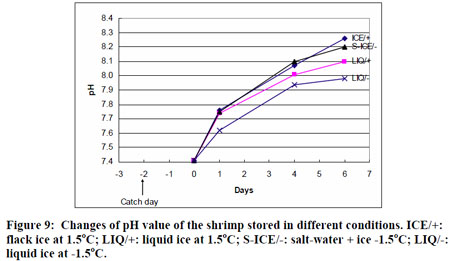

(shrimp at the 0.6 % salt level) Note seawater averages around 3% salty, or 2550 mg/3 oz serving. Contrary to popular belief, human blood is not as salty as the ocean, but closer to 0.9%. And shrimp, depending on the species and where it is harvested, runs close to 0.2-0.4%. So at 460 mg, these crustaceans are one and a half to three times as salty as fresh live shrimp. Not surprisingly, taste test panels confirm people prefer salty food, so the high sodium levels are simply "meeting customer expectations." Also, the pH of shrimp changes during storage. Live shrimp mirrors seawater levels, around 7.5 pH, but quickly rises to 8.3 pH. This is markedly different behavior than with hooved meat, which often becomes more acidic at slaughter, and takes weeks of aging to partly recover. Since typical solutions of baking soda achieve a pH of 8.3, adding baking soda to modern shrimp will not raise the pH- one reason to more critically examine the "chemical pH" hypothesis.

To avoid confusing the chemistry of baking soda with other pre-exisiting chemical treatments, less adulterated shrimp is necessary. We located an alternative (and even more expensive) manufacturer packaging untreated shrimp (except for a bit of salt). Interestingly, without additives, these shrimp did incur more drip loss and were limper after defrosting, than their chemically enhanced bretheren. They all measured a pH of ~8.5, as expected.

We defrosted, shelled, deveined and de-legged the shrimp. Four different treatments were applied, based on their similarities to standard Chinese cooking recipes.

In a half hour the additives would penetrate a few mm, and then continue almost to the center during cooking3. Especially if butterflied. The shrimp were all patted dry, weighed and then steamed over gently boiling water for exactly 5 minutes. Weighed immediately after steaming, cooled in the fridge, then weighed again. And the results:

The "acceptable" textured shrimp were not at all rubbery, but simply firm. The "very tender" lye shrimp were smooth, but not soft or mushy. The baking soda shrimp had patches of foamy meat on the surface, easily revealed with dye. Any of these shrimp would make a fine meal- the fact is, if you don't overcook, additives are unnecessary4.

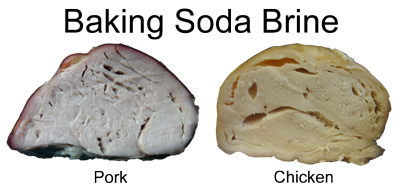

But what about the mechanical vs the chemical hypothesis? In terms of water-loss (juiciness), all methods proved identical. On the one hand, the more alkaline the treatment, the softer the shrimp. But, given the high pH of commercial shrimp, pH alone many not be the explanation. And we did notice bubbles in the two alkaline shrimp - but smaller bubbles than in the pork and chicken examples above. Yet lye does not contain CO2. An apparent mystery. My goal with kitchen science experiments is to use easily obtainable tools and techniques, so the reader can reproduce the results at home. Even the food science literature rarely converges on issues of tenderness in meat- there is too much variability in nature, and the chemistry is frankly complex. In my experiments I required a microscope and histological stains to visualize the underlying science, so rather than publishing the results, I am on a quest to find alternative, easily accessible measurement techniques. Will rewrite the article, and identify the culprit, when that quest is met....

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Additional articles on kitchen science can be found HERE. 1 They also found uses for boric acid, MSG, red yeast rice for coloring, and so on. Early molecular gastronomists! But this tendency may have gotten out of hand in modern China, where industrial chemicals are too often introduced for convenience or to save money, with detrimental health effects 2 Since the molecular weight of salt (58 gm/mole) is nearly that of baking soda (84 gm/mol), the sodium levels are similar in both tests. However, note it is the chlorine, not the sodium, which is responsible for swelling meat proteins so they can retain more juices. 3 Shrimp have an open circulatory system, which is why larger molecules can diffuse inward faster than in meat. Photos illustrating this distinction to follow. 4 Curiously, a day later the plain shrimp was also tender, and worked out better in a shrimp salad. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |

In stir-fry, thin slices of food are quickly cooked over intense heat. The advantages of stir-fry are legion: cooking is rapid, so precious fuel is preserved. The sliced food is often marinated to absorb spices and other flavors- and as we've demonstrated in previous articles, large

In stir-fry, thin slices of food are quickly cooked over intense heat. The advantages of stir-fry are legion: cooking is rapid, so precious fuel is preserved. The sliced food is often marinated to absorb spices and other flavors- and as we've demonstrated in previous articles, large  Fortunately, over the centuries itinerant Chinese kitchen "chemists"1 developed a solution to the rubber-shrimp problem. They discovered many chemicals, such as lye (sodium hydroxide NaOH) and baking soda (NaHCO3) tenderizes food. Lye water is often added to noodles (for flavor, color and texture) or to rice (to soften and congeal during steaming). Baking soda is sprinkled on chicken or shrimp in a technique known as "velveting", to encourage tenderness, while also extending the cooking window from 15 seconds to a minute or more.

Fortunately, over the centuries itinerant Chinese kitchen "chemists"1 developed a solution to the rubber-shrimp problem. They discovered many chemicals, such as lye (sodium hydroxide NaOH) and baking soda (NaHCO3) tenderizes food. Lye water is often added to noodles (for flavor, color and texture) or to rice (to soften and congeal during steaming). Baking soda is sprinkled on chicken or shrimp in a technique known as "velveting", to encourage tenderness, while also extending the cooking window from 15 seconds to a minute or more.