| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| what goes up, .. |

|

Nov. 2013

Chocolate or vanilla? Shaken or stirred? Salad or fries? And should you smoke a brisket with the fat-cap UP or DOWN?

Such questions aren't matters of mere taste or fashion, but divide the smoking community into distinct, warring camps. Fame, bragging rights and trophies are all at risk. So what is the right decision? At first glance, neither choice appears optimal. There are very good reasons to trim ALL of the fat from BOTH sides of a brisket, rendering the entire question moot:

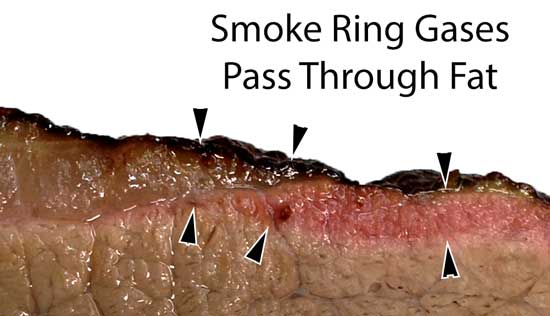

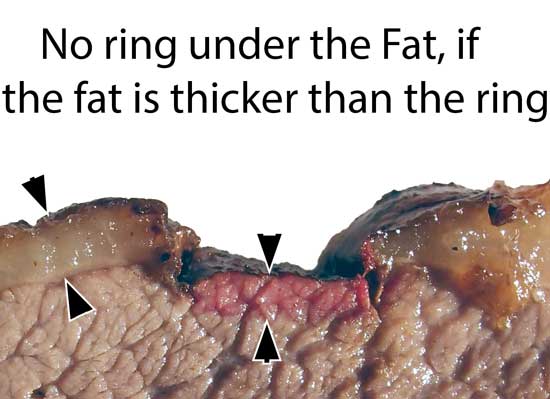

Smoke gases (carbon monoxide and nitric oxide) pass through fat almost as rapidly as through meat. So the ring will appear under fat, minus the thickness of the fat.

On the other hand (claim its proponents), fat is the key to taming brisket's reputation as a dry and stringy cut. Important enough to compensate for every one of the purported deficiencies.

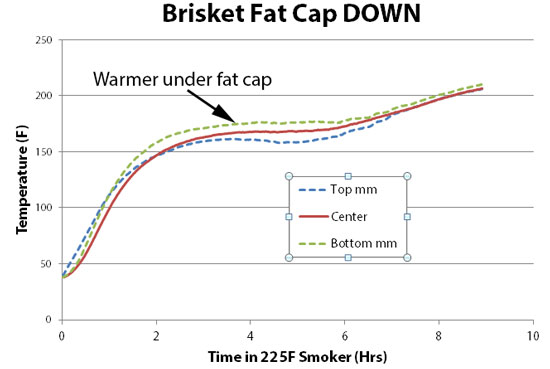

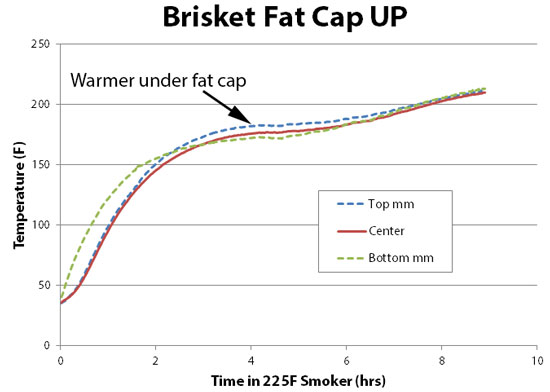

Of these three claims, only the third is consistently true. Brisket muscles are long bundles of protein. After smoking, when the collagen breaks down into water absorbing gelatin and the juices are partly expelled, gaps appear between these bundles. These gaps act like straws, sucking up whatever juice and fats it rests in after cooking. Perhaps 5% of its cooked weight. Or about 1/6th of the moisture lost during smoking1. And fat lost is flavor lost. Especially fat that has absorbed a bit of smoke from the fire. But, alternatively you could have trimmed your brisket of fat, placed the excess fat in a tray during smoking and added this rendered flavor bomb to the foil during the crutch. "No" to the cap, and "yes" to the fat. Perhaps obtaining the best of both worlds. But first, let's examine these two warring positions more closely. When meat is cooked over an open fire, it really does make sense to cook fat side down. Not because fat is a good insulator- in fact, fat is a modest insulator and meat cooks FASTER when you leave the fat cap on, but as a sacrificial layer of char that can be easily sloughed off before eating. In another article, we discuss how fat's insulation value is at most 50% greater than raw meat (e.g. seals accumulate blubber as a food larder, not to stay warm). As the meat cooks and loses moisture, the two values draw even closer together. In any case, most smokers heat "indirectly", that is, via hot air and not directly from the flames. So "down' and "up" are equally hot. More critically, fat blocks evaporation. And evaporation cools off meat. We can see the effect of a 3/8" thick fat-cap during smoking in this graph. Thermocouples were inserted in the middle of a 1.5" thick brisket flat, a mm from the surface on the trimmed side, and a mm into the meat below the fat cap on the other side.

(measured in a PID controlled electric smoker, with careful placement so airflow was uniform across the top and bottom of the brisket) Note how the temperature on the trimmed meat side (blue dotted line) rises fastest in the first hour of cooking. Nothing stands between the heat and the meat. On the other hand, the fat-cap side (green dotted line) does act like a bit of insulation by rising more slowly. Though it's not due to fat's insulation value- the thermocouple was 3/8" away from the surface, and thus farther from the heat than on the naked side. As the brisket warms and starts to evaporatively cool, the temperature below the fat cap (green dotted line) begins to rise. And the temperature on the trimmed side (blue) dropped due to evaporative cooling. During the stall, it is 20 degrees warmer on the fat side than the naked side. When we repeated the experiment with the fat-cap UP in the same smoker at the same time, the fat-cap side is again the hotter side after the initial hour or two.

So much for insulating the meat from the heat! What about idea that rendering fat coats the sides and bottom of the meat? Does fat-cap UP slow evaporation, and make the meat juicier? Well, it turns out oil and water do not mix. And there is a constant flow of watery juices from inside the meat to the surface. Together, this has the effect of blocking fat from entering during cooking. It also slightly blocks water from leaving the meat- often the fat-cap UP briskets stall a bit higher in temperature2. More importantly, fat will gather and drip off the bottom of the meat, and that has the effect of slightly reducing the smoke ring and washing away smoke flavor as it condenses on the glistening surface. As to tenderness? Well, we all recognize that fat-cap up, fat-cap down, meat hung vertically, and no fat-cap at all techniques each have won major barbecue contests and earned plaudits from backyard cooks. In fact, many pitmasters have switched caps mid-way through their career, with happy results. In my own tests, the fat cap plays very little role compared to the Texas Crutch or high humidity (assuming you remove the meat when perfectly cooked). Personally, I always trim off the fat-cap before smoking. My brisket technique is relatively simple:

Like most conflicts, facts won't settle the issue. So let us know how you prefer to trim a brisket before smoking, by filling out this two question survey by clicking HERE. A summary of responses will appear after submission.

|

|

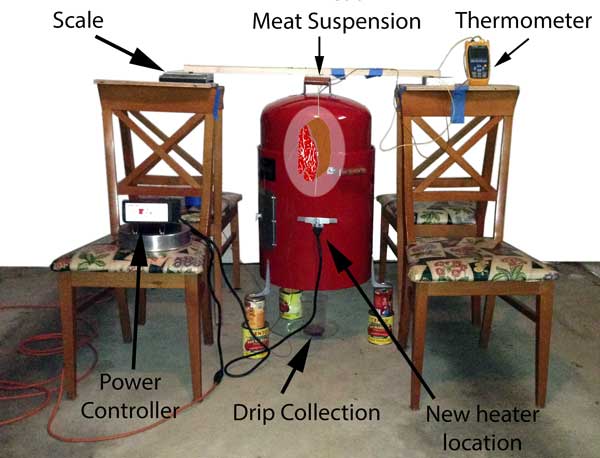

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 We've also measured how much juice emerges from pork and brisket (with the fat cap on and off). Turns out they are more similar than not. The apparatus consisted of a Brinkman electric smoker where I relocated the heating element to the center of the chamber. I also removed the bottom and elevated the entire apparatus. Because hot air rises, the top of the smoker remains at a consistent 225F, while the bottom was near room temperature. Any juice or fat that dripped off the meat, bypassed the electric elements and were collected in a plastic high walled container (to catch splats). The container was periodically replaced and the fats and juices separately weighed on a precision scale. Calibration runs confirmed less than 1 in 20 drips were lost or evaporated.

(the meat's position is shown for clarity- there is no window through the smoker wall) To eliminate any pooling on the surfaces, I hung the meat vertically on a metal skewer, like the arrangement in a pit barrel smoker. The skewer was attached to a string and then to a lever and then to a digital scale. Which is complicated way to say I measured the weight loss during cooking. Finally, the temperature of the meat was measured just below the surface and in the center- the average temperature is used in these plots. In the case of a four pound pork shoulder, the weight loss is divided into three categories- fat loss, drip loss and evaporative loss:

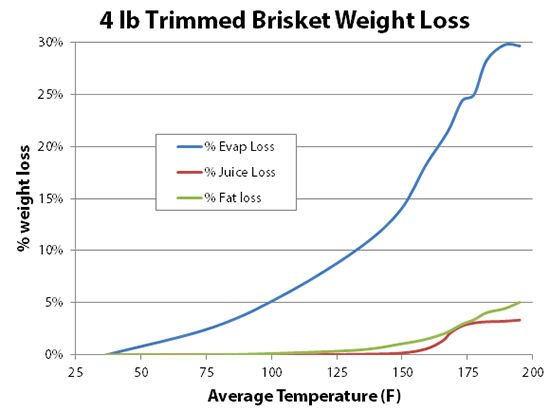

There are few interesting things to note about this curve. First, meat starts losing weight by evaporation almost immediately- this is why you have to take evaporative cooling into account at all times during cooking! The weight loss speeds up significantly around 135F. Which is exactly when collagen wrapping the meat fibers start to shrink and squeeze out meat juices. In ground meat, the juices flow profusely between the grinds at 135F, but in a solid cut of meat, it takes time for the juices to emerge. Also, pork fat begins to render around the same temperature. By 175F, the juice loss has abated, and evaporation begins to slow as well. The total weight loss is around 33% by the time the pork is done. This chart is a great guide to when to Texas Crutch. One criteria is the amount of juice collected in the foil which will later be absorbed or added to a glaze. For example, if you remove the pork at 175F (around 16% evaporative loss) there is still around another 8% of the original weight to be evaporated and collected in the foil. Perhaps 10 oz of juice from an 8 lb shoulder. If you want more juice or more fat to be retained inside the meat, crutch at a lower temperature. Many people crutch at around 150F, just when the juice and fat flows are about to increase signficantly. We also measured brisket with fat cap on and off. The rectangular brisket has much surface area than the cylindrical pork shoulder, so evaporation dominates dripping. Still there is little difference between the two, and and differences are small compared to the variations between individual cuts of meat, and from cook to cook:

Unlike pork, beef fat begins to render around 115F. But the curves are otherwise similar. As is the total weight loss from all three categories. In other words, what goes on inside the muscle dominates moisture loss. Fat is a much less critical player. 2 Total cooking speed will depend on whether the cap is up or down, and will vary depending on the smoker. My workhorse MAK pellet smoker is cooler below the grate due to obstruction by the heat spreader, and airflow is higher above the grate. So fat-cap DOWN often cooks fastest, as the hot moving air flowing over the fat-free top surface evaporates juices more quickly, reducing the length of the stall. But, in a big ugly BPS drum smoker, the situation is reversed and fat-cap down cooks a bit faster. Of course, if you wrap at 145F instead of 170F and spend much of the time in the crutch, smoking time is less critical. Fat Cap Survey

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |